My Week With the Lakota

My new friend, Phil Little Thunder, dancing at the Washington Monument in 2017.

My new friend, Phil Little Thunder, dancing at the Washington Monument in 2017.

In the early morning of September 3, 1855, 600 U.S. soldiers commanded by General William S. Harney surrounded a peaceful Lakota Sioux village—about 250 people whose tipis were pitched along a clear stream in the Sandhills of northwestern Nebraska. On Harney’s order, the village of a revered Lakota leader named Little Thunder was destroyed. Lodges were set ablaze and the belongings of Little Thunder’s people were plundered or burned.

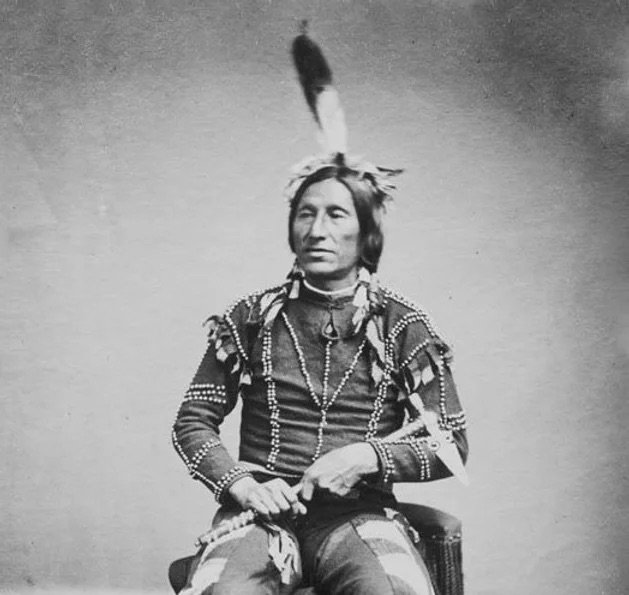

Many if not most of the 86 Lakota people killed along Blue Water Creek that day were women and children. Seventy other women and children were taken prisoner and marched 140 miles by Harney’s troops across the grasslands to be imprisoned at Fort Laramie, Wyoming. The Lakota leader, Little Thunder, who survived the massacre, in his later years.

The Lakota leader, Little Thunder, who survived the massacre, in his later years.

In the past several months, what is now known as the Blue Water Massacre has become a passionate interest of mine. The more I learned about it, the more the atrocity seemed to echo the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921—another important and horrific moment in American history that has remained largely unknown.

There are two grim bookends to what are known as the Indian Wars—the period when the Lakota, the people of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, fought fiercely to keep their ancestral lands and to preserve an ancient and beautiful way of life. At the same time, agents of the U.S. government sought to exterminate the people, clearing them away on behalf of the millions of white settlers hungry for land that white Americans believed was their God-given right.

The Wounded Knee Massacre in December 1890 was the final bookend. The Blue Water Massacre was the first, a watershed moment but one that largely has been lost to history.

But some know. Some remember. On a hot Sunday afternoon a few weeks ago, the 168th anniversary of the Blue Water, I was invited to join a prayer circle and healing ceremony in the shade of huge cottonwood trees. The spot was just a few yards from the winding creek whose waters remain pristine today, just a few yards from where the tipis of Little Thunder’s people had stood. I was deeply honored to stand with the descendants of Little Thunder, General Harney and their non-Native friends as they remembered, sang and prayed for the spirits that the Lakota believe still linger at the site.

During the ceremony, the music of Phil Little Thunder’s song, drum and flute was carried away by the wind.

“I would just like to say thank you to everybody for being here, for being here for us, for all of us,” said another descendant, Karen Little Thunder. “You’re helping us to lighten this heavy load that we carry.”

Late in the ceremony, I told the circle about my friendship with a holy man named Fred Rogers.

“Fred once told me, ‘There is a loving mystery at the heart of the universe that yearns to be expressed,’” I said. “If he were here today, he would say that there has rarely been a more beautiful expression of that mystery than what has happened today.” With Phil Little Thunder a few weeks ago.

With Phil Little Thunder a few weeks ago.

The next day I drove three hours north, onto the South Dakota reservation of Little Thunder’s people, the Rosebud Lakota. In that place the Blue Water Massacre is living history, an open wound. The week I spent on the reservation was one of most meaningful, beautiful and exhausting of my life. So much to learn. So much to see. So much to feel.

I was treated with great kindness by Karen, Phil and Gary Little Thunder. They have devoted their lives to remembering what happened and to the continuation of the rituals and ceremonies of their culture.

I was invited to the home of Peter Gibbs, once a senior curator at the British Museum in London, who married a Lakota woman and many years ago moved to the Rosebud reservation. For the last several decades, he has used his unique skill set on behalf of the people, and in the 1990s was among the first to bring the massacre to the attention of later generations.

I enjoyed a lively dinner conversation with Phil Two Eagle, executive director of the Sicangu Lakota Treaty Council.

I was privileged to sit with Lakota elders Victor Douville and Duane Hollow Horn Bear, listening to them speak ancient wisdom.

On my final day in Indian Country, I made the two-hour drive west from the Rosebud reservation to a broad valley near Pine Ridge, S.D., where on December 29, 1890, 250 Lakota men, women and children were slaughtered by soldiers of the 7th Cavalry. Such was the somber conclusion to my short visit, the memorial and graveyard at the place called Wounded Knee, the final bookend.

A man named Paul Soderman was with me that day at Wounded Knee and every day previous. He is descended from General Harney. In remarkable acts of love and atonement and reconciliation, Paul has devoted decades to honoring the voices of the Lakota and learning their history, culture, language and spiritual ways—to the extent that he and his wife, Cathie, have been adopted into Karen Little Thunder’s family. Karen Little Thunder and Paul Soderman at the Fort Laramie National Historic Site in 2015.

Karen Little Thunder and Paul Soderman at the Fort Laramie National Historic Site in 2015.

Paul generously agreed to travel with me to the reservation, a mentor, guide and indispensable friend as I entered a world so different than my own.

I met and was also befriended by Brad Upton, a descendant of the Colonel James W. Forsythe, who commanded the Army troops responsible for the Wounded Knee Massacre. Brad, too, is a remarkable example of the possibilities of healing and reconciliation available to those willing to face the past.

My gratitude extends to Pat Gamet, who owns land where the Blue Water Massacre took place, Kylee Warren, and sisters Jean Jensen and Dianne Greenwald and their families, who grew up along the Blue Water, live there still, and for years have been an integral part of the healing.

I have no idea where this journey of mine might lead. Perhaps I can play a small role in restoring this atrocity to history, similar to the role I was fortunate to play when I wrote the New York Times bestselling book, The Burning, about the Tulsa Race Massacre. I also would love to help celebrate and elevate the remarkable Lakota culture.

For now, I’m deeply grateful for my experiences of a few weeks ago. As I said, it was one of the most challenging weeks I’ve spent, and one of the most beautiful. I am a different person for it, better somehow.

I’ve said this from my first days in Tulsa more than two decades ago—for white people, there is nothing to fear and everything to gain by being willing to learn the real stories, by being willing to face the difficult truths of our past. In doing so we are healed and deepened as human beings. My short time with the Lakota is just one more example of that.

On my travels last week, I gathered bits and pieces of the Lakota language. Anpetu waste (Good day.) Mitakuye Oyasin (We are all related.) As it turns out, there is no Lakota word for goodbye. Instead, they say, Toksa ake (I’ll see you again.)

But my favorite new phrase is this one. Taku Wakan Skan Skan (Something sacred is in motion.) As I remember my recent experiences with the Lakota, it certainly felt that way to me.

--

I'm Proud Of You, the stage play based on my memoir of the same name, opens on Thursday night, October 26, at Circle Theatre in downtown Fort Worth. Circle hosts the official world premiere on Saturday night, October 28. For the full schedule of the play and to purchase tickets, visit this link: https://bit.ly/3PIaBQq

To purchase the memoir I’m Proud of You or any of my books, visit: https://amzn.to/3tVoAH0